PRINCIPLES OF LEARNING THEORY IN EQUITATION

Explore the 10 First Principles of Horse Training by The International Society for Equitation Science.

Uncover the foundational guidelines rooted in scientific research and expert knowledge.

ISES 10 training principles

Human and horse welfare depend upon training methods and management that demonstrate:

1. Regard for human and horse safety

- Acknowledge that horses’ size, power and potential flightiness present a significant risk

- Avoid provoking aggressive/defensive behaviours (kicking /biting)

- Ensure recognition of the horse’s dangerous zones (e.g hindquarters)

- Safe use of tools, equipment and environment

- Recognise the dangers of being inconsistent or confusing

- Ensure horses and humans are appropriately matched

- Avoid using methods or equipment that cause pain, distress or injury to the horse

“Disregarding safety greatly increases the danger of human-horse interactions”

2. Regard for the nature of horses

- Ensure welfare needs: lengthy daily foraging, equine company, freedom to move around

- Avoid aversive management practices (e.g. whisker-trimming, ear-twitching)

- Avoid assuming a role for dominance in human/horse interactions

- Recognise signs of pain

- Respect the social nature of horses (e.g. importance of touch, effects of separation)

- Avoid movements horses may perceive as threatening (e.g jerky, rushing movements)

“Isolation, restricted locomotion and limited foraging compromise welfare”

3. Regard for horses’ mental and sensory abilities

- Avoid overestimating the horse’s mental abilities (e.g. “he knows what he did wrong”)

- Avoid underestimating the horse’s mental abilities (e.g. “It’s only a horse…”)

- Acknowledge that horses see and hear differently from humans

- Avoid long training sessions (keep repetitions to a minimum to avoid overloading)

- Avoid assuming that the horse thinks as humans do

- Avoid implying mental states when describing and interpreting horse behaviour

“Over- or underestimating the horse’s mental capabilities can have significant welfare consequences”

4. Regard for current emotional states

- Ensure trained responses and reinforcements are consistent

- Avoid the use of pain/constant discomfort in training

- Avoid triggering flight/fight/freeze reactions

- Maintain minimum arousal for the task during training

- Help the horse to relax with stroking and voice

- Encourage the horse to adopt relaxed postures as part of training (e.g. head lowering, free rein)

- Avoid high arousal when using tactile or food motivators

- Don’t underestimate horse’s capacity to suffer

- Encourage positive emotional states in training

“High arousal and lack of reinforcement may lead to stress and negative affective states”

5. Correct use of habituation/desensitization/calming methods

- Gradually approach objects that the horse is afraid of or, if possible, gradually bring such aversive objects closer to the horse (systematic desensitization)

- Gain control of the horse’s limb movements (e.g step the horse back) while aversive objects are maintained at a safe distance and gradually brought closer (over-shadowing)

- Associate aversive stimuli with pleasant outcomes by giving food treats when the horse perceives the scary object (counter-conditioning)

- Ignore undesirable behaviours and reinforce desirable alternative responses (differential reinforcement)

- Avoid flooding techniques (forcing the horse to endure aversive stimuli)

“Desensitization techniques that involve flooding may lead to stress and produce phobias”

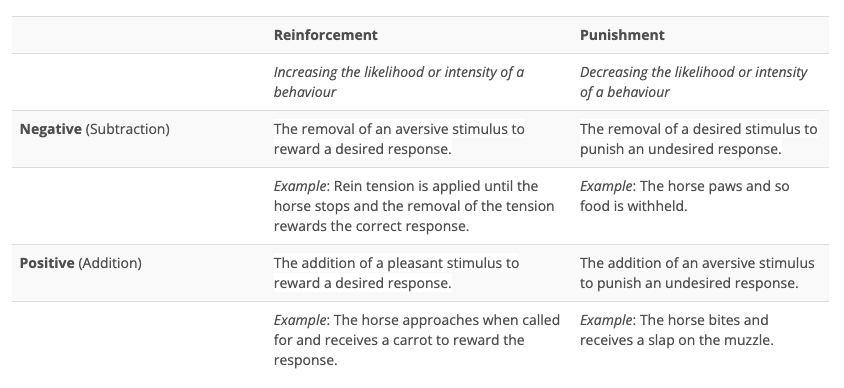

6. Correct use of Operant Conditioning

- Understand how operant conditioning works: i.e. performance of behaviours become more or less likely as a result of their consequences.

- Tactile pressures (e.g. from the bit, leg, spur or whip) must be removed at the onset of the correct response

- Minimise delays in reinforcement because they are ineffective and unethical

- Use combined reinforcement (amplify pressure-release rewards with tactile or food rewards where appropriate)

- Avoid active punishment

“The incorrect use of operant conditioning can lead to serious behaviour problems that manifest as aggression, escape, apathy and compromise welfare”

7. Correct use of Classical Conditioning

- Train the uptake of light signals by placing them BEFORE a pressure-release sequence

- Precede all desirable responses with light signals

- Avoid unwanted stimuli overshadowing desired responses (e.g. the horse may associate an undesirable response with an unintended signal from the environment)

“The absence of benign (light) signals can lead to stress and compromised welfare”

8. Correct use of Shaping

- Break down training tasks into the smallest achievable steps and progressively reinforce each step toward the desired behaviour

- Plan training to make the correct response as obvious and easy as possible

- Maintain a consistent environment to train a new task and give the horse the time to learn safely and calmly

- Only change one contextual aspect at a time (e.g trainer, place, signal)

“Poor shaping leads to confusion”

9. Correct use of Signals/Cues

- Ensure signals are easy for the horse to discriminate from one another

- Ensure each signals has only one meaning

- Ensure signals for different responses are never applied concurrently

- Ensure locomotory signals are applied in timing with limb biomechanics

“Unclear, ambiguous or simultaneous signals lead to confusion”

10. Regard for Self-carriage

- Aim for self-carriage in all methods and at all levels of training

- Train the horse to maintain:

- gait

- tempo

- stride length

- direction

- head and neck carriage

- body posture

- Avoid forcing any posture

- Avoid nagging with legs, spurs or reins i.e. avoid trying to maintain responses with relentless signaling.

”Lack of self-carriage can promote hyper-reactive responses and compromise welfare”

Click on the images or the flags to download posters of the ISES Training Principles in a growing number of languages.

A message from the Dutch W.O.W. team to all ISES members and friends of Equitation Science…

When we developed our interpretation of the ISES 10 training principles, to our surprise, it became not only a poster with the translation of the 10 principles each in 10 separate pictures but much more: while having fun developing several tools for practical use, we had developed a whole concept. This first part of the W.O.W. concept contains several elements and various attractive tools to teach novice riders of all ages and their (pony-club) teachers, trainers, instructors. In addition to the ISES – W.O.W. poster on the ISES website, the other materials we developed can be found on our website. Currently, we are working on additional elements for more experienced riders and equine professionals.

Horse welfare while working with horses, we can’t make it easier but we can make it more clear and fun to learn and teach. We do hope we have awakened your curiosity, please visit our website and/or share this link www.horsewelfare.com on your social media accounts (for the Dutch, all files are already translated, see www.paardwelzijn.nl).

Examples of Desensitisation Techniques

Systematic Desensitisation

Counter Conditioning

Overshadowing

Approach Conditioning

Stimulus Blending

The quadrant of reinforcement and punishment